The Story of Legendary Asian American Artist, Tyrus Wong

Bambi in Pastel by Tyrus Wong

Bambi, the Disney Movie

Many of us have either seen or heard of Disney’s classic animated film, Bambi. The story of the brave, orphaned deer and his faithful rabbit sidekick, has captured the heart of countless Americans since its 1947 release. However, few know the inspiring story of the person who was a major influence on Bambi’s visual aesthetic, Tyrus Wong, a Chinese-born American artist. In a time period when the Chinese were heavily discriminated against and not seen as American, Wong broke societal standards with each stroke of his brush. Weaving Chinese art and Chinese presence into American culture, Tyrus Wong is a symbol of perseverance and resistance for the Asian community.

““Wong broke societal standards with each stroke of his brush.””

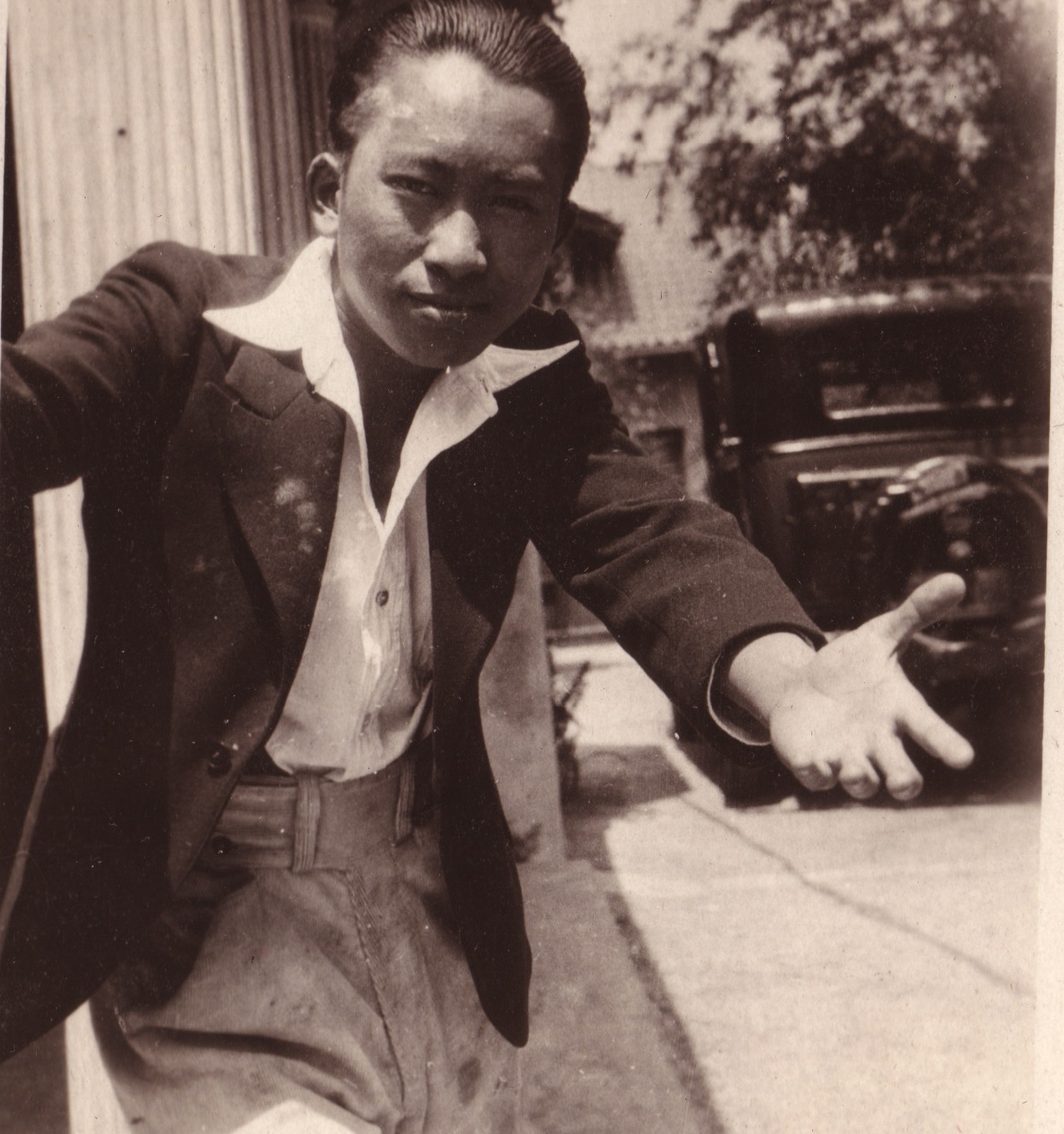

Tyrus as a young man; courtesy of the Wong family

Tyrus Wong was born in the Guangdong province of China and immigrated to America with his father in the late 1910s. As a result of the Chinese Exclusion Act, Wong was separated from his father at nine years old and lived alone for a month at an immigration station on Angel Island, a center designed to trick and prevent immigrants from entering the US. Tyrus was a self-proclaimed trouble maker at school, playing hooky and doodling instead of paying attention in class. At the time, Asian immigrants often worked at laundromats and restaurants; however, Wong received financial support from his single father to pursue an education at an art school. Living under extreme poverty, Wong practiced painting using newspaper and water.

Even at a young age, Tyrus Wong’s work stood out from the rest. He became an extremely versatile artist over the span of his career, mastering watercolor, pastel drawing, calligraphy, and even kite-making. One of Wong’s greatest talents was applying minimalism to convey a story. As Tyrus narrates in the opening of Tyrus, a documentary about his life, “If you do a painting with five strokes instead of ten, you can make your painting sing.”

In one of his early pieces, Wong reimagines the softness of a snow monkey’s fur with a smudging technique, juxtaposing the soft texture with rough strokes that form a tree branch. Where soft meets hard, the snow monkey hangs precariously from the branch with one arm. Wong may have related to this monkey who is painted with a gentle smile despite dangling so high up in the air. From getting incarcerated at Angel island to not being properly credited for his artistic contributions at Disney and Warner Bros until he was in his 90s, each experience with racism and prejudice did not stop Wong from creating beautiful art that captivates and inspires.

Tyrus Wong’s 1933 Snow Monkey; Still from from “Tyrus” film

““Wong may have related to this monkey who is painted with a gentle smile despite dangling so high up in the air.””

Tyrus Wong passed away in 2016 at 106 years old, though his strong legacy remains. ACDC is proud to be screening the documentary, Tyrus, at this year’s opening night of Films at The Gate. Directed by award-winning filmmaker Pamela Tom, Tyrus honors the life of an Asian American trail-blazer in the 20th century. The movie presents Wong’s life holistically, addressing AAPI life during immigration exclusion, housing discrimination, and the Japanese internment camp.

Join us on August 23rd at our annual Films at the Gate event to witness the manifestation of startlingly beautiful and deeply intricate artwork and the life of the humble Chinese immigrant who created them. The screening is scheduled for 8pm and is free to the community.

Meet Pamela Tom at a special pre-screening reception that includes a light dinner and cash bar! All proceeds benefit ACDC’s youth leadership program, A-VOYCE.

Colorized black and white photo of Tyrus painting; courtesy of PBS